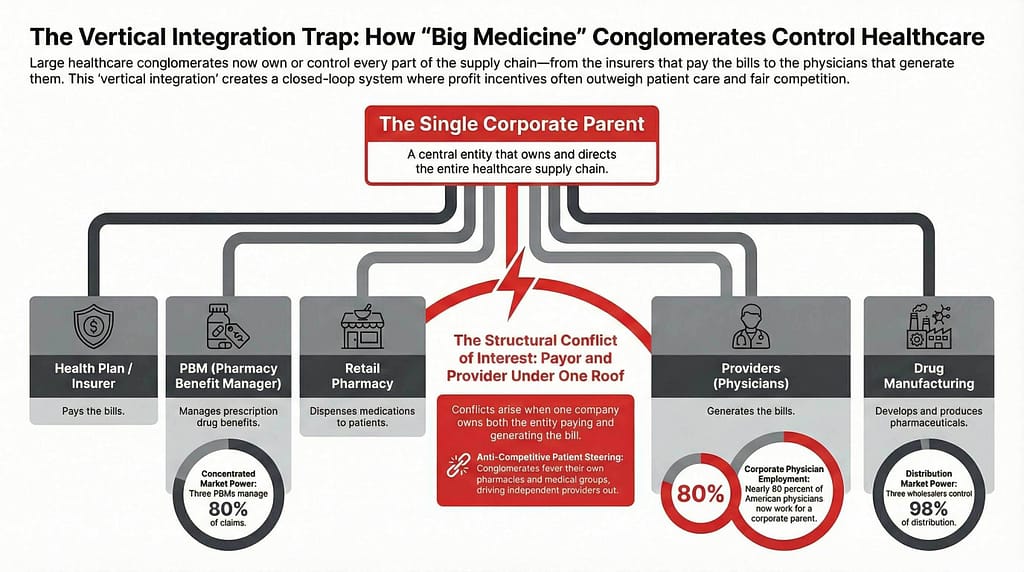

We’ve been writing about vertical integration for years now. In our 2025 managed care trends report, we asked a simple question: Is it a conflict of interest to own everything? The FTC or state in which a hospital system is based often won’t allow any health system to own more than 50% of the inpatient beds. Yet, an insurance company can have 90% market share and then vote on what the rate increase will be for their participating hospitals. In Kansas, congratulations, that’s often 1-2% when costs are over 5% per year.

Congress might have woken up from their lazy slumber and stopped looking at their phones recently.

Senators Josh Hawley and Elizabeth Warren have introduced the Break Up Big Medicine Act, a bipartisan proposal aimed at vertically integrated healthcare conglomerates — the insurers, PBMs, pharmacies, physician practices, specialty groups, and wholesalers increasingly operating under the same corporate roof.

In the press release, Senator Hawley said:

“Americans are paying more and more for healthcare while the quality of care gets worse and worse. In their quest to put profits over people, Big Pharma and the insurance companies continue to gobble up every independent healthcare provider and pharmacy they can find. Working Americans deserve better. This bipartisan legislation is a massive step towards making healthcare affordable for every American.”

The bill would prohibit a parent company from owning both a health insurer and a medical provider, a PBM and a medical provider, or a drug or device wholesaler and a medical provider. In plain speak, if you own the entity that pays the bill and the entity that generates the bill, Congress believes that may represent a structural conflict. We, as patients or family members, have all experienced this to be true – we just may not have noticed it.

This didn’t start with Big Medicine

Hawley and Warren previously collaborated on the Patients Before Monopolies Act, legislation aimed at strengthening antitrust enforcement in healthcare and tightening merger standards. That earlier effort focused on preventing dominant players from consolidating further under the assumption that scale automatically improves outcomes.

The Break Up Big Medicine Act goes further. Instead of simply scrutinizing future mergers, it questions whether certain ownership combinations should exist at all. It challenges the structure, not just the transactions. That’s a meaningful shift.

We’ve seen where unchecked vertical integration can lead

If you want to understand where unchecked vertical integration can lead, look at Ma Bell.

Before its breakup, “The Phone Company” controlled local companies, long-distance networks, the physical copper lines, switching infrastructure, equipment manufacturing, and the research division. It owned the entire telecommunications pipeline.

The argument was familiar: vertical integration improves coordination, ensures quality, and increases efficiency. That’s true, but when one company controls the network, the hardware, and the rules of access, competition narrows. In 1982, the federal government forced AT&T to divest its local operating companies. The phones worked just fine; the issue was structural dominance and the lack of quality and responses to customer service issues.

That’s the lens for healthcare. The question isn’t whether vertically integrated insurers can operate efficiently, it’s what happens when one entity controls too many layers of the ecosystem.

How exactly did we get here?

Vertical integration has been expanding over the last decade

In that time, large health insurers have done far more than negotiate reimbursement rates. They acquired physician practices, management services organizations, ambulatory surgery centers, home health providers, PBMs, and retail pharmacy chains. Nearly 80% of physicians now work for a corporate parent, and the three largest PBMs manage roughly 80% of prescription drug claims.

That level of consolidation changes incentives whether anyone intends it to or not — and now we have Cordavis.

When your health insurer manufactures the drug

CVS Health launched Cordavis to develop and commercialize biosimilars in coordination with an insurer-owned PBM and retail pharmacy ecosystem. That development deserves attention because it pushes vertical integration further upstream.

When the same corporate structure

- Designs the health plan

- Sets the formulary

- Determines prior authorization rules

- Owns the PBM

- Owns the retail pharmacy, and

- Participates in drug manufacturing

we are no longer simply discussing alignment. We are looking at vertical compression of the entire pharmaceutical supply chain.

If a PBM can favor its own manufactured biosimilar, the retail pharmacy dispenses that product, and the health plan steers volume through benefit plan design or formulary, the incentives are clear. When an insurer becomes a manufacturer, cost control and market dominance align.

We’ve been tracking this for a while, and now Congress has noticed.

Why this matters for providers

If you are a physician group or health system negotiating with a vertically integrated payor, you are not negotiating with a neutral third party. In most markets, you are negotiating with an organization that owns provider practices, ambulatory centers, telemedicine providers, or even full health systems that are your direct competition.

You’re sitting across the table discussing reimbursement rates with a company that employs physicians competing with you down the street or over a Zoom.

When the same corporate parent

- Designs the health plan

- Sets reimbursement rules

- Controls prior authorization

- Owns the PBM

- Dispenses the drug, and

- Employs competing providers

negotiations are now sharing information with the competition.

If your payor owns a competing cardiology group with ASC or ortho group with imaging, PT, and ASC, how do site-of-care policies evolve? If they manufacture a specific biosimilar, how does that influence formularies and utilization management?

You don’t need conspiracy theories to see the tension. You just need to understand incentives.

Even when individuals act in good faith, structures create pressure, so when a payor also owns competing providers in your market, it is difficult to argue the playing field is level.

Will this pass?

That’s another question.

The insurers and vertically integrated healthcare corporations targeted by this legislation are among the largest companies in the country or the world depending on how we categorize. They have scale, lobbying power, capital, and deep relationships across both parties. Structural breakups are extraordinarily difficult to execute politically and legally. This does NOT mean providers should do nothing — write, advocate, vote, and force lobbying entities to take a stronger stance on this!

It would be naive to assume this bill sails through Congress, but the significance isn’t limited to whether it passes. The fact that bipartisan legislation is openly questioning structural ownership models tells you something important: vertical integration is no longer viewed as automatically benign. The regulatory temperature has changed. Just remember, this Congress is one of the least productive in history.

Even if this specific bill stalls, the scrutiny won’t disappear.